Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut declared herself pharaoh, ruling as a man would for over 20 years and portraying herself in statues and paintings with a male body and false beard. Hamburger game online. As a sphinx, Hatshepsut displays a lion's mane and a pharaoh's beard. Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) was the first female ruler of ancient Egypt to reign as a male with the full authority of pharaoh. Her name means.

When he died, his son—Hatshepsut’s stepson—became pharaoh, even though he was just three years old. Hatshepsut ruled in his name, but he was still considered the only pharaoh. But when Thutmose III was about eight years old, she took the throne herself and officially became his coruler around 1473 B.C. Some historians think she made the move because other people wanted to steal the throne, and she knew if they were both pharaohs they would be too powerful to overthrow. Hatshepsut and Thutmose III would rule together as pharaohs for the next 22 years. Considered one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs—man or woman—Hatshepsut brought great wealth and artistry to her land. She sponsored one of Egypt’s most successful trading expeditions, bringing back gold, ebony, and incense from a place called Punt (probably modern-day Eritrea, a country in Africa).

She secured her legacy by building structures that still stand today. She added two hundred-foot-tall obelisks at the great temple complex at Karnak. (One is still intact.) And she built the mortuary Temple of Deir el Bahri, a structure with several floors of columns in front, where she’d eventually be buried.

Heroes of might and magic iv video game. The cause of Hatshepsut's death is not known. Her mummy was missing from its sarcophagus when her tomb was excavated in the 1920s. There are several theories about her demise, including that she either suffered from cancer or was murdered, possibly by her stepson. No theory has been proved, nor has her body been conclusively identified.Hatshepsut, the elder daughter of the 18th-dynasty king and his consort Ahmose, was married to her half brother, son of the lady Mutnofret. Since three of Mutnofret’s older sons had died prematurely, Thutmose II inherited his father’s throne about 1492 bce, with Hatshepsut as his consort.

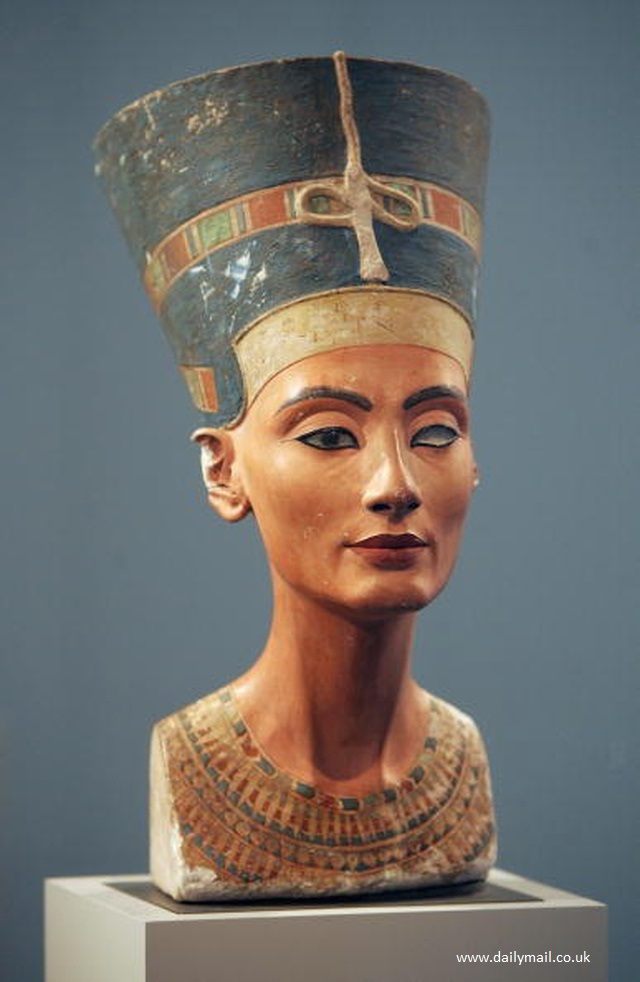

Hatshepsut bore one daughter, Neferure, but no son. When her husband died about 1479 bce, the throne passed to his son, born to, a lesser harem queen. As Thutmose III was an infant, Hatshepsut acted as regent for the young king.For the first few years of her stepson’s reign, Hatshepsut was an entirely conventional regent. But, by the end of his seventh regnal year, she had been crowned king and adopted a full royal titulary (the royal adopted by Egyptian sovereigns). Hatshepsut and Thutmose III were now corulers of Egypt, with Hatshepsut very much the dominant king. Hitherto Hatshepsut had been depicted as a typical queen, with a female body and appropriately feminine garments. But now, after a brief period of experimentation that involved combining a female body with kingly (male) regalia, her formal portraits began to show Hatshepsut with a male body, wearing the traditional regalia of kilt, crown or head-cloth, and false beard.

To dismiss this as a serious attempt to pass herself off as a man is to misunderstand Egyptian artistic convention, which showed things not as they were but as they should be. In causing herself to be depicted as a traditional king, Hatshepsut ensured that this is what she would become.Hatshepsut never explained why she took the throne or how she persuaded Egypt’s elite to accept her new position. However, an essential element of her success was a group of loyal officials, many handpicked, who controlled all the key positions in her government.

Most prominent amongst these was Senenmut, overseer of all royal works and tutor to Neferure. Some observers have suggested that Hatshepsut and Senenmut may have been lovers, but there is no evidence to support this claim. Get exclusive access to content from our 1768 First Edition with your subscription.Traditionally, Egyptian kings defended their land against the enemies who lurked at Egypt’s borders. Hatshepsut’s reign was essentially a peaceful one, and her was based on trade rather than war. But scenes on the walls of her, in western, suggest that she began with a short, successful military campaign in. More-complete scenes show Hatshepsut’s seaborne trading expedition to, a trading centre (since vanished) on the East African coast beyond the southernmost end of the., animal skins, processed, and living myrrh trees were brought back to Egypt, and the trees were planted in the gardens of Dayr al-Baḥrī.Restoration and building were important royal duties. Hatshepsut claimed, falsely, to have restored the damage wrought by the (Asian) kings during their rule in Egypt.

She undertook an extensive building program. In Thebes this focused on the temples of her divine father, the national god Amon-Re ( see ).

At the temple complex, she remodeled her earthly father’s, added a barque shrine (the Red Chapel), and introduced two pairs of obelisks. At in Middle Egypt, she built a rock-cut temple known in Greek as Speos Artemidos. Her supreme achievement was her Dayr al-Baḥrī temple; designed as a funerary monument for Hatshepsut, it was dedicated to Amon-Re and included a series of chapels dedicated to, and the royal ancestors. Hatshepsut was to be interred in the, where she extended her father’s tomb so that the two could lie together. Dayr al-Baḥrī: temple of Hatshepsut Detail of statues on the third terrace of the temple of Hatshepsut at Dayr al-Baḥrī, Thebes, Egypt. © Ron Gatepain Toward the end of her reign, Hatshepsut allowed Thutmose to play an increasingly prominent role in state affairs; following her death, Thutmose III ruled Egypt alone for 33 years. At the end of his reign, an attempt was made to remove all traces of Hatshepsut’s rule.

Her statues were torn down, her monuments were defaced, and her name was removed from the official king list. Early scholars interpreted this as an act of, but it seems that Thutmose was ensuring that the succession would run from Thutmose I through Thutmose II to Thutmose III without female interruption. Hatshepsut sank into obscurity until 1822, when the decoding of hieroglyphic script allowed archaeologists to read the Dayr al-Baḥrī inscriptions.

Initially the discrepancy between the female name and the male image caused confusion, but today the Thutmoside succession is well understood.

- суббота 04 апреля

- 90